Georgian is a language from the Kartvelian family spoken in the South Caucasus.

Language

The Lord's Prayer in Old Georgian (Adysh Gospels, 9th c.)

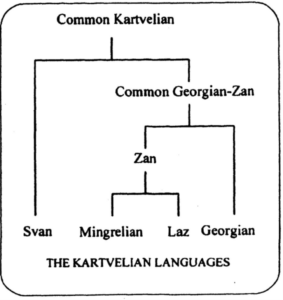

Georgian language, like many Caucasian languages, is not related to any other language. Georgian is related to its group, Kartvelian. Kartvelian comprises Georgian and unwritten Svan, Mingrelian, and Laz languages. While Svan and Mingrelian are predominantly spoken in the mountainous and coastal part of western Georgia, the Laz language is spoken by the minority of the Pontic shores of Turkey.

Georgian language, like many Caucasian languages, is not related to any other language. Georgian is related to its group, Kartvelian. Kartvelian comprises Georgian and unwritten Svan, Mingrelian, and Laz languages. While Svan and Mingrelian are predominantly spoken in the mountainous and coastal part of western Georgia, the Laz language is spoken by the minority of the Pontic shores of Turkey.

Georgian is spoken by roughly 4 million. Svan is spoken by about 40,000 in the high mountainous area of northern-western Georgia. Mingrelian is spoken by more than 300,000 inhabitants of western Georgia, stretching between the Black Sea coast and the Tskenistwkali River. Although Mingrelia borders Svaneti, the inhabitants of these two regions cannot understand each other’s languages unless they use Georgian. Georgian functions as a lingua franca and is a literary language for Svan and Mingrelian. The Laz language is spoken predominantly by the minority of Turkey (estimated to be roughly 50,000) who inhabit the Black Sea shore stretching from Pazar (Atina) to Sarpi. The Laz and Mingrelian languages are mutually intelligible. However, the opinions among the scholars differ on whether the Mingrelian and Laz are the same language or if they should be treated as separate languages but related to each other.

The following features distinguish the Kartvelian group from the Caucasian language groups:

- The use of relative pronouns and conjunctions together with finite verb forms in subordinate and relative constructions

- The absence of noun classes

- Formal rather than functional ergativity

- The exclusive use of postpositions in locative expression

Script

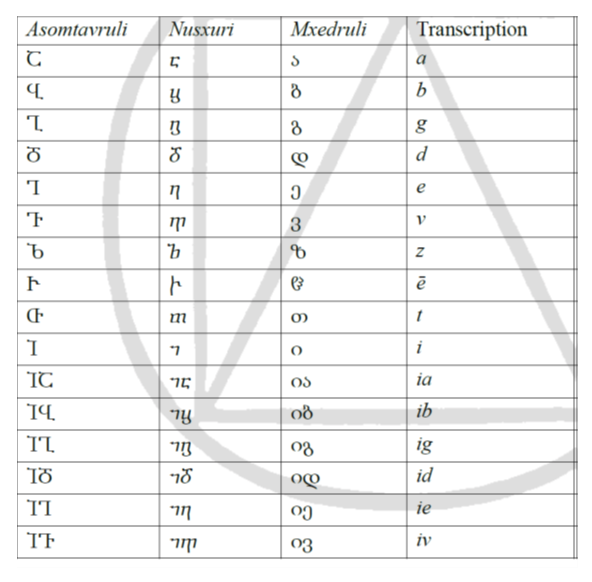

Three scripts have been used to write Georgian:

1) Asomtavruli (majuscules) also styled as mrgvlovani - “rounded”

2) Nusxuri minuscules (often referred to as “ecclesiastical” or middle Georgian script)

3) Mxedruli minuscules

The Georgian script (Asomtavruli) was invented towards the end of the fourth century in Palestine in the monastic milieu by learned Georgian monks. The alphabet was a tool to turn Georgian from a spoken to a written language and translate vast Christian literature into Georgian. The invention of the Georgian alphabet also replaced Greek as a language of the liturgy. Although it is almost certain that the creation of the alphabet happened decades after the Georgian royal family’s conversion to Christianity (4th century AD), the Georgian historiographical tradition, the Life of the Kings, ascribes the invention of Georgian script to a legendary king Parnavaz, who ruled eastern Georgian kingdom of Kartli in 4th–3rd century BCE.

The Georgian script (Asomtavruli) was invented towards the end of the fourth century in Palestine in the monastic milieu by learned Georgian monks. The alphabet was a tool to turn Georgian from a spoken to a written language and translate vast Christian literature into Georgian. The invention of the Georgian alphabet also replaced Greek as a language of the liturgy. Although it is almost certain that the creation of the alphabet happened decades after the Georgian royal family’s conversion to Christianity (4th century AD), the Georgian historiographical tradition, the Life of the Kings, ascribes the invention of Georgian script to a legendary king Parnavaz, who ruled eastern Georgian kingdom of Kartli in 4th–3rd century BCE.

The earliest surviving sample of the Georgian script is a mosaic inscription made on the floor of a Georgian monastery in Jerusalem. The second oldest evidence of the Georgian alphabet is dedicatory inscriptions made on the wall of Bolnisi Sioni church in eastern Georgia in the 480s.

Literature

The development of written Georgian is traditionally categorized into three stages.

- Old Georgian – the written texts of various types composed between the 5th and 11th centuries

- Middle Georgian – various types of literary compositions (secular and ecclesiastical) dating from the 12th up to the end of the 18th century

- Modern Georgian – from the 19th century up to the modern period

The earliest extant piece of Georgian literature is a hagiographical narrative, the Life and Martyrdom of Holy Queen Šušanik, authored by Iakob Curtaveli and composed towards the end of the 5th century.

The oldest original historical writings are the Conversion of Kartli (7th century) and the Life of the Georgian Kings (8th century). While The Conversion is a short chronicle, sometimes just listing the names of the Georgian rulers, the Life of the Kings is a proper historiographical text that focuses on the lives and deeds of the rulers of the eastern Georgian kingdom of Kartli from the legendary first king Parnavaz (4th century BCE) up to the second half of the fifth century AD. In the same period was composed the Life of Vaxt’ang Gorgasali, a historiographical text full of legendary and fictional stories that portrays the biography of king Vaxt’ang who ruled in eastern Georgia in the second half of the fifth century, in the period when the Sasanian Iran held the sway over the eastern Caucasus. The earliest Georgian historiographical and hagiographical texts bear witness to eastern Georgia’s strong cultural and social ties with Sasanian Iran and the Near Eastern world. After the rise of Islam and the disintegration of Sasanian Iran, the Christian Roman (Byzantine) empire’s cultural and political influence increased. This found its reflection in the Georgian literature (hagiography and historiography) composed after ca. 800. Giorgi Merčule’s Life of Grigol Xanӡteli (10th century), and historiographical texts, the Chronicle of Kartli (11th century) and Life of Davit, King of Kings (12th century), demonstrate Georgia’s strong ties with the Christian Roman empire and its’ secular and ecclesiastical elite’s orientation on Constantinople. For instance, the Life of Ilarion, and the two vitae – the Life of Ioane and Euthymios the Athonites and the Life of Giorgi the Athonite – that portray the lives of Georgian learned monks and their intellectual and translating activities, were composed in the monastic environs of the Byzantine empire, Constantinople and Mount Athos.

Located at the crossroads and the edge of the Christian and Islamic worlds, Georgian literature was not immune to foreign influences. From the late twelfth century, Georgian learned men started to exhibit akin interest in Persian and Near Eastern literature and poetry. Šota Rustaveli’s epic poem The Knight in the Panther Skin is a good example of how original Georgian literature could accommodate Persian and Near Eastern literary forms and imagery. The cosmopolitan nature of the medieval Georgian kingdom is also reflected in two laudatory court poems, the Abdulmesiani [servant/slave of the Messiah] and In Praise of King Tamar composed at the court of a female monarch, queen Tamar (r. 1184–1210). While magnifying the reign of the first female monarch in Georgian history and eulogizing her achievements, the authors of these poems display close acquaintance with Byzantine as well as Persian and Arabic literature.

Most notable works

- The Life and Martyrdom of Holy Queen Šušanik is the earliest extant piece of Georgian literature composed towards the end of the fifth century (in the 480s) by an eyewitness of the events, Iakob Curt’aveli. The hagiographical narrative portrays the martyrdom of a noblewoman, Šušanik, from the hands of her apostate husband, Varsk’en. In order to gain more power and prove his loyalty to the Sasanian king of kings, Varsk’en traveled to Iran and converted to Zoroastrianism. Varsk’en also promised the Sasanian monarch to convert his entire family.

- The Life of St. Nino – a vita of an apostolic female saint of Georgia, responsible for converting king Mirian III and his wife, queen Nana, to Christianity. Various redactions of Nino’s life were made through the Middle Ages, including the 12th century metaphrastic version by Monk Arsen.

- The Life of Ioane and Euthymios the Athonites composed by Giorgi the Athonite in the 1050s, at the Georgian monastery of Iviron on Mount Athos. The hagiographical vita portrays the lives of the first two hegoumenoi of Iviron. A particular emphasis is placed on how Iviron was turned into the center of Georgian manuscript production and translation activities.

- The Life of Giorgi the Athonite by Giorgi Mcire (the Minor) was also composed on Mount Athos and describes the life of a learned monk who became a leader of Iviron Monastery. Giorgi the Athonite revived the tradition of producing and copying Georgian manuscripts which had declined at Iviron in the 1030s. He is responsible for translating a large number of Greek texts and authors into Georgian. The Life of Ioane and Euthymios and Life of Giorgi the Athonite are the most valuable pieces of Georgian literature that allow one to have an insight into Byzantine-Georgian cultural and political relations from the end of the tenth up until the second half of the eleventh century. Furthermore, these two hagiographical texts are primary sources for understanding the scope of manuscript production and intellectual activities that had thrived in the Georgian monastery located in the Byzantine empire.

- Kartlis Cxovreba/ the Life of Kartli – the corpus of Georgian historical writings, containing various texts written between the 8th and 14th centuries. Kartlis Cxovreba, often referred to as Georgian Royal Annals, tells the history of Georgian kingship from the 4th century BCE up to the end of the Mongol domination in Georgia (14th century).

- Šota Rustaveli’s The Knight in the Panther Skin is an epic poem and a masterpiece of secular Georgian literature composed towards the end of the 12th century. According to Rustaveli’s testimony, his long poem was commissioned by queen Tamar. The Knight in the Panther Skin’s plot revolves around the imagined world of the Near East, and events occur in the kingdoms of Arabia, India, and China.

External links

Georgian texts (Medieval and Modern) online – TITUS Thesaurus Indogermanischer Text- und Sprachmaterialien https://titus.uni-frankfurt.de/indexe.htm?/texte/texte2.htm

Corpus of Georgian Inscriptions – TITUS

https://titus.uni-frankfurt.de/texte/etcg/cauc/ageo/inscr/carcera/carce.htm

Epigraphic Corpus of Georgia –