English, which has been in use for 1500 years and is spoken today by approximately 450 million people all over the world, belongs to the West-Germanic branch of the Indo-European family. In the medieval period, we distinguish two phases which are traditionally referred to as Old English and Middle English.

Old English language (5th c – 11th c)

The Lord's Prayer in Old English (Matthew 6.9 (WSCp, 11th c.))

Fæder ure

þu þe eart on heofonum,

si þin nama gehalgod.

Tobecume þin rice.

Gewurþe ðin willa on eorðan swa swa on heofonum.

Urne gedæghwamlican hlaf syle us todæg.

And forgyf us ure gyltas swa swa we forgyfað urum gyltendum.

And ne gelæd þu us on costnunge,

ac alys us of yfele. Soþlice.

Old English originated from the dialects spoken by Germanic tribes from continental Europe (traditionally referred to as Jutes, Angles, Saxons and possibly also Frisians) who began settling in Britain in the mid-5th century, following the end of Roman rule on the island.

Old English language looks nothing like English we know today. For example, compare the Old English sentence Heofona rice is geworden þæm menn gelic þe seow god sæd on his æcere with its Modern English equivalent: The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a man who sowed good seed in his field). Structurally, Old English was much closer to languages like modern German, as it was highly inflected. Words carried grammatical meaning through various endings, which often combined multiple functions. For instance, in nouns and adjectives, a single ending could indicate gender, number, and case. Old English nouns, in particular, distinguished four cases.

Compared to later stages of English, Old English had relatively few loanwords – only about 3 percent of its vocabulary, compared to 70 percent in Modern English. When loanwords did appear, they were primarily borrowed from Latin. However, Old English also relied heavily on its own productive word-formation patterns to create new words rather than adopting foreign terms. For example, instead of borrowing præpositio from Latin, its components were carefully translated to form the Old English word foresetnyss.

Towards the end of the Old English period, the language began to be influenced by Old Norse due to Viking invasions, though this influence became fully apparent only in the Middle English period. The Vikings first raided Britain in the 8th century, drawn by the wealth of monasteries along the Northumbrian coast. Over time, they began settling in conquered territories and gradually intermarried with local Anglo-Saxon women.

In the 9th century, following King Alfred’s successful military campaigns against the Vikings, a settlement agreement was reached. Known as the Treaty of Wedmore, it allowed the Vikings to remain in England under the condition that they convert to Christianity and retreat to the northeastern regions. This area later became known as the Danelaw.

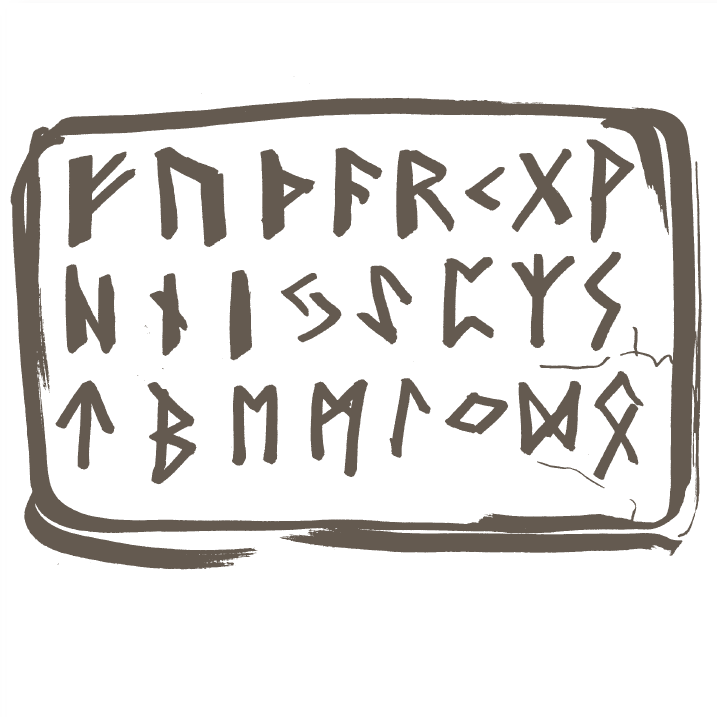

Old English Script

Old English was originally written in a Runic script, developed in Scandinavia and brought to England by the Germanic tribes. The Runic alphabet, known as futhark after its first six letters, consisted of angular characters made up of short lines, making them convenient for carving into hard surfaces such as wood or stone.

In England, the original Scandinavian alphabet was modified to reflect pronunciation changes that distinguished Old English from Scandinavian languages. For example, the Scandinavian rune ᚫ (ansuz), originally representing the sound a (and named after the Germanic word for "god"), was pronounced as o in Old English when followed by n or m. To reflect this shift, the rune’s shape was modified to X, leading to the Anglo-Saxon Runic alphabet being known as futhorc.

With the Christianization of the Anglo-Saxons in the 6th century—primarily through Irish missionaries—the Latin alphabet was gradually adopted. However, for a time, both writing systems coexisted, as seen in runic inscriptions on some Christian monuments. Notable examples include the Ruthwell Cross, which features a passage from the Old English poem The Dream of the Rood carved in runes (see Ruthwell Cross), and the Franks Casket, a whalebone casket adorned with runic inscriptions blending pagan and Christian themes (see Franks Casket).

Since the Latin alphabet lacked letters for certain Old English sounds, modifications were made:

- Ð/ð ("eth"): Developed by Irish scribes, it represented both the voiced and unvoiced th sounds (as in this and thank).

- Þ/þ ("thorn"): Borrowed from the Runic alphabet, it initially represented the unvoiced th sound but was later used interchangeably with eth.

- Ƿ/ƿ ("wynn"): Another borrowing from the Runic alphabet, used for the w sound.

- Ȝ/ȝ ("yogh"): A special form of g, representing the sounds g, j, and h.

- Æ/æ ("ash"): A digraph used for a vowel sound unique to Old English, its name deriving from the runic alphabet.

Old English Literature

The earliest Old English poetry is characterized by heroic epics, the elegiac genre, a small amount of lyric poetry, and fragments of folk literature, including riddles, incantations, and proverbs.

Old English poetry was influenced by the traditions of Germanic wandering bards, known as scops, who composed verses on various themes for different occasions and performed them for a patron who rewarded their services with lavish gifts (such experience of a wandering bard is captured in the early Old English poem Widsith).

From a formal point of view, Old English poems use an irregular meter consisting of two half-lines, each containing two stressed syllables. Instead of rhyme, Old English poetry relied on alliteration—the repetition of the same sound at the beginning of words—following precise rules. Another typical feature of Old English poems is the use of metaphor to create a distinctive kind of compound words known as “kennings”. These expressions, often resembling riddles, were a prominent feature in Old Norse poetry as well. For example, in Old English poetic texts, one might encounter the expression bānhūs (literally “bone-house”) to mean “body”, or hwælweg (“whale-way”) to refer to the “sea”.

Prose, often written in Latin than Old English, included religious and philosophical works, sermons, homilies, saint’s lives, educational texts and chronicles.

Most of Old English literary works have been preserved in four major codices. The Exeter Book (c. 975), named after the cathedral where it is kept, contains poems such as the above mentioned Widsith, and the following elegiac poems: Deor where a rejected scop laments that his benefactor has forsaken him after favouring a new singer. The Wanderer, told from the perspective a lone warrior who has lost his lord, kin and home, wandering through a desolate world, reflecting on the transience of life and impermanent nature of earthly glory. The Seafarer, narrated by a lone sailor who describes the harshness of life at sea, enduring cold, isolation, and suffering. As the poem progresses, the focus shifts from earthly struggles to a spiritual reflection on the fleeting nature of worldly pleasures and the importance of seeking salvation in God. The Exeter Book also contains a collection of Old English riddles. These combine wit, wordplay, and metaphor to describe objects, creatures, or phenomena in an enigmatic way. They often rely on personification, double meanings, and vivid imagery, challenging the reader to decipher their hidden subject.

The manuscript known as Cotton Vitellius (c. 1000, sometimes also called the Nowell Codex or the Beowulf manuscript) is housed in the British Museum and contains two poetic works: the epic Beowulf and Judith, an adaptation of the Old Testament Book of Judith which describes the beheading of Assyrian general Holofernes by the eponymous widow.

The Junius Manuscript (c. 1000) includes poems inspired by the Bible (Genesis, Exodus, Daniel, Christ and Satan), attributed to the first known English poet, Cædmon. According to legend, he was an illiterate herdsman who received the divine gift of composing songs about creation in a dream.

The Vercelli Book is a codex that contains both prose and religious poetry, most notably the poem The Dream of the Rood, an Old English religious poem that presents a visionary account of Christ’s crucifixion from the perspective of the Cross (the "Rood"). The poem is structured as a dream vision, in which the speaker sees a glorious, jewel-adorned tree that reveals itself as the Cross upon which Christ was crucified. The Rood then recounts its own experience, describing how it was once a humble tree before being chosen as the instrument of Christ’s sacrifice. It shares in Christ’s suffering, feeling the nails and torment, but also in His triumph over death. The poem blends heroic and Christian imagery, portraying Christ as a noble warrior who bravely embraces His fate. In the end, the dreamer is inspired to seek salvation and looks forward to eternal life.

The most important and well-known Old English text is the epic poem Beowulf, composed between approximately 675 and 850, which draws on oral traditions and legends of the Germanic peoples, mixing pagan motifs with Christian themes. The narrative follows the titular hero, Beowulf, who embodies the ideal warrior ethos, characterized by bravery, loyalty, and a sense of duty to protect his people from monstrous threats. The poem's structure interweaves Beowulf's battles against Grendel, Grendel's mother, and a dragon, each representing different facets of evil and chaos that the hero must confront to maintain societal order and stability.

Beowulf is not the only Old English epic that has survived. Other epic compositions include heroic poems celebrating battles against Vikings, such as The Battle of Brunanburh and The Battle of Maldon.

Authors

Most Old English literature is anonymous; however, a few authors are known by name. Besides the aforementioned Cædmon, another notable Anglo-Saxon poet is Cynewulf, who is credited with religious poems such as Christ, Juliana, The Fates of the Apostles, and Elene. The preacher, teacher, and ecclesiastical writer Ælfric (d. c. 1020) is best known as the author of Lives of Saints. The priest and preacher Wulfstan (d. 1032) wrote numerous homilies, the most famous of which is the fiery and apocalyptic Sermo Lupi ad Anglos (The Sermon of the Wolf to the English).

Latin works

The flourishing of learning in Northumbrian monasteries during the 7th century gave rise to several outstanding Latin authors, the most notable being the historian and theologian known as the Venerable Bede (Beda Venerabilis). His most extensive work, the five-volume Ecclesiastical History of the English People (Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum), chronicles England’s history from the time of Julius Caesar up to the year 731 and became an often-sought source for medieval chroniclers. Some of the stories he recounts evolved into national legends—such as the tale of Saint Gregory, who was so moved by the angelic face of an Anglo-Saxon boy in a Roman slave market („They are not Angles, but angels!“) that he resolved to spread Christianity in their land.

Translations

King Alfred the Great (r. 871–899) was not only a shrewd military leader but also played a significant role in the restoration of learning and literacy, which had suffered greatly due to Viking attacks. He oversaw and is credited with translations of key Latin works into Old English, including Pastoral Care by Pope Gregory I, Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius, and Soliloquies by St. Augustine, often adapting them to suit his audience. Alfred also initiated the creation of the first systematic chronicle, known as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which represents the first national history written in a vernacular language in Western Europe. It has been preserved in seven manuscripts, the Peterborough manuscript being the latest, ending in the year 1154.

Middle English (11th c – 15th c)

The Lord's Prayer in Middle English (Wycliffe, 1384)

Oure fadir that art in heuenes,

Halewid be thi name;

Thi kyngdoom come to;

Be thi wille don, in erthe as in heuene.

Yyue to vs this dai oure breed ouer othir substaunce,

and foryyue to vs oure dettis, as we foryyuen to oure dettouris;

and lede vs not in to temptacioun, but delyuere vs fro yuel. Amen.

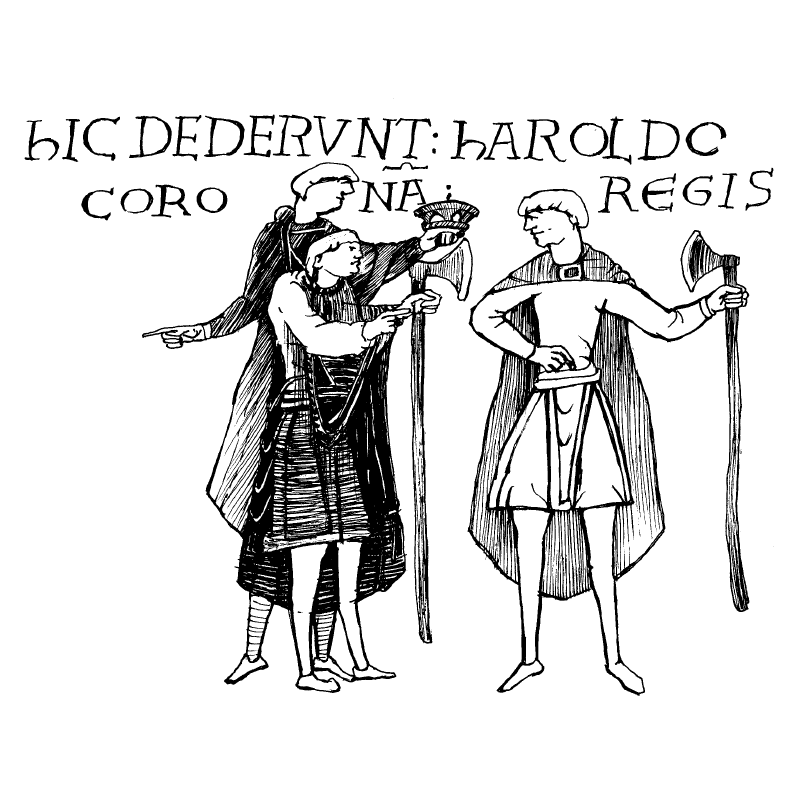

Middle English was a period marked by the continuing influence of Old Norse as well as the influence of French after the Norman duke William conquered England in 1066. His victory resulted in English language being ousted from its role of a language of the court and governmental and legal affairs for as long as 200 years. English, then considered rude and barbarous, was spoken by the lower classes of peasants, artisans, labourers and lower clergy.

Close contact between Old English and Scandinavian languages in the mixed households lead to the gradual simplification of the Old English grammatical system which eventually lost most of its endings. In nouns, only the ending which marks plural survived as the system of nominal inflections for gender and case had ceased to function by the beginning of the thirteenth century (see video below).

The influence of other languages did not only result in the simplification of the English grammar, but it also greatly enriched its vocabulary. While Latin mainly supplied scholarly words, Old Norse provided many common, everyday words such as egg, husband, ill, leg, take. This was facilitated by the fact that English and Scandinavian had a shared Germanic origin and were therefore mutually comprehensible. The closeness between the two languages is underscored by English borrowing from Old Norse also some pronouns, conjunctions and prepositions. Such borrowings are rare because words like these are usually not replaced by words of foreign origin. From the early thirteenth century, vowel changes made the differences between the Old English pronoun system hard for the speaker to produce and the listener to hear: masculine pronoun “he” (he) sounded a lot like “hie” (they) and “heo” (she). This led to the borrowing of the Old Norse pronoun þei (they) in the thirteenth century. This new pronoun could be used of a single person of unknown gender from its earliest written attestations.

During Middle English period, a great number of words were borrowed into English from French. The first borrowings came from the Norman dialect of French (the conquering Normans were, in fact, Scandinavians in disguise who settled in the north of France in the 9th century). The first loanwords were linked to the government of the country by Norman lords (that is why English legal vocabulary is largely French in origin; words like justice, prison or court all come from French). Even at the time when English in the 14th century regained its status as the official language and the language of prominent literary works, French was still considered prestigious. But this time, French words were flowing into the English vocabulary from the Central Frech dialect spoken in Paris rather than from the Norman French which had begun to gain ridicule. French words borrowed in the later Middle English period are especially words linked with scholarship, fashion, arts and food (e.g. college, robe, verse or veal).

Middle English Script

Anglo-Saxons developed a fairly uniform written language which was used for legal, historical and literary documents. But when English was replaced by French in these roles, there was no longer need for standard spelling. This had dramatic consequences on the orthography because scribes did not follow any unified spelling system but did their best to reflect in spelling how they spoke (for example, the word “merry” could be spelled in a dazzling number of variants as miry, mirye, mury, murye, miri, mirre, mirie, mirrie, mirry, myrrie, myrry, mery, merye, mere, meri, merey, merie, merrye, meary, merrie…).

In Middle English, however, spelling underwent changes due to the influence of French scribes who arrived in England after the Norman Conquest and brought with them their own spelling conventions. A selective list of some of these changes is below.

Changes in the vowel system meant that the letter “æ” was no longer required.

The letter “ð” dropped out of use completely, being completely interchangeable with “þ”. That letter then began to lose out to the digraph /th/ during the 14th century. The letter þ changed its shape in late 11th century handwriting, looking either like a ƿ or a y. So, when you walk on an English street and see a pseudo-archaic shop sign of the likes “Ye Olde Sweet Shoppe”, note that “ye” is meant to be read as “þe” (= “the”)!

Among other conventions of Norman scribes were the introduction of the digraph “sh” for the sound [š] (Old English used “sc” instead, as in Englisc) and “ch” for the sound [č] (Old English used the letter c as in cild, child).

Letter “c” appeared in some words for the sound [s], as it is common in French. This is why we write “mice” with “c” and not with “s” as in “mouse”.

Under the influence of French, the letter “u” began to represent the sound of the modern letter “v” in certain circumstances, so the word “over” could then be written ofer as in Old English or ouer. The letter “g” came to represent the sound /g/, “qu” replaced “cw” in words like “queen” (in Old English cwēn). This word also demonstrates the practice in ME spelling to double the vowel to indicate its length.

By 1500, printed books begun to circulate in England thanks to William Caxton’s printing press (established in 1476). This groundbreaking invention contributed to shaping a written standard of English by the end of the Middle English period, based on the London (East Midland) dialect.

Middle English Literature

After the Norman Conquest, Middle English literature was influenced by the complex linguistic situation in England. While French was the prestigious language of the court and English was spoken by the common people, English lacked a standardized written form for a long time. Four main Middle English dialects developed—Northern, Midlands, Southern, and Kentish—and it was common that each writer essentially used their own local dialect. In the 14th century, however, a standardized form of English gradually developed based on the London dialect. This emerging standard became the language of education, was introduced into the legal system, and was used by prominent writers such as Geoffrey Chaucer and John Gower.

Among the authors writing in French in England was, for example, Marie de France, known for her lais – epic songs on courtly and adventurous themes. She composed them in octosyllabic couplets, a hallmark of French poetry. This rhyming structure based on eight-syllable lines in rhyming pairs gradually ousted the traditional alliterative verse used in English poetry (although alliterative verse experienced a revival in 14th-century poetry from the Midlands and Northern England, in seminal works such as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight or Piers Plowman).

In addition to French, Latin, the language of scholars and clergy, continued to be used in England for writing ecclesiastic, didactic or philosophical works. Yet it was also the primary language for historical records, such as the chronicle Historia Regum Britannie by the Benedictine monk Geoffrey of Monmouth. He based his chronicle on Germanic legends and other folklore, but also used his own imagination, as seen in the creation of the story of King Arthur. This contributed to the chronicle becoming one of the primary historical sources until the early 17th century.

Middle English literature written in English is remarkably diverse, as manuscripts reveal a vast array of genres in both prose and verse. Below is a selection of some notable examples:

Chivalric romance originated from French epic poems, the chansons de geste, and is enriched with the element of courtly love which emerged in the 12th century in troubadour poems in the southern France, blending Christian morality with adventure and supernatural elements. The main hero is usually a valiant knight who serves not only his lord but also the lady of his heart. To prove himself worthy of her love, he embarks on a series of adventures that test his chivalry and moral excellence.

English courtly romances draw on themes of French, Celtic, and Classical origin. French material focuses on stories from the cycle of Charlemagne, Celtic material centres on King Arthur, and Classical tales are derived from ancient antiquity, focusing on Troy or Alexander the Great.

Among the most important Arthurian romances are:

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (late 14th century, anonymous)

One of the finest Middle English romances which explores themes of honour, temptation, and human fallibility. In alliterative rhyme, it tells the story of Sir Gawain, who accepts a challenge from the mysterious Green Knight. Gawain beheads him, but the knight collects his head and informs Gawain that he must travel to his domain a year later to receive a return blow. On Christmas Eve, Gawain arrives at a castle where he is warmly welcomed by the lord and his beautiful lady. Each day, the lord goes hunting, and in the evening, the two men exchange whatever they have gained during the day. Gawain stays at the castle with the lady, behaving courteously while resisting her temptations. On the first evening, he exchanges a kiss for the lord’s hunting prize, on the second evening, two kisses, and on the third, three. However, he conceals the fact that the lady has given him a magic girdle that has the power to make him invulnerable. When the time comes for Gawain’s encounter with the Green Knight at the chapel, he survives with only a slight wound in his neck. Yet, he feels ashamed for having hidden the green girdle. He keeps it as a reminder of his failure and pride, and in solidarity, the other knights and their ladies begin wearing it as well.

Le Morte d'Arthur (c. 1470, Sir Thomas Malory)

A monumental prose work compiling Arthurian legends, Malory’s Le Morte d'Arthur recounts the rise and fall of King Arthur, the exploits of Lancelot and the other knights of the Round Table, the tragic love affair between Lancelot and Guinevere, and the downfall of Camelot. It became the definitive English version of the Arthurian myth.

Social (the Estates) satire: Social satire in Middle English literature is a genre that uses humour, irony and exaggeration to critique social structures, corruption, and human folly. It often targets the clergy, aristocracy, and common folk, exposing hypocrisy, greed, and moral decay. While it overlaps with allegory and didactic literature, its primary aim is to entertain while provoking reflection and reform.

Perhaps the most famous example of social satire is Geoffrey Chaucer‘s (c. 1343–1400) Canterbury Tales, a selection of verse narratives told by fictional pilgrims on their way to the shrine of Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral. The form was heavily inspired by Italian Renaissance poetry in its use of an approximation of iambic pentameter and end rhyme, as well as the frame narrative. Each tale reflects the storyteller’s social class and personality. The General Prologue introduces a wide range of characters, from the noble Knight to the bawdy Miller and the bold, worldly and outspoken Wife of Bath who challenges medieval gender norms by openly discussing sex and female dominance, asserting that women should have sovereignty in marriage.

One of the dominant genres of storytelling was allegory in which abstract concepts, moral lessons, or religious truths were represented through symbolic characters, events, and settings. These narratives often serve a didactic purpose, guiding readers toward moral or spiritual enlightenment. Examples of allegorical poems are:

Piers Plowman (14th c, William Langland)

This alliterative poem follows the dream-visions of a character named Will, who searches for a true Christian life in a corrupt world. The poem critiques the clergy, government, and social injustice, making it an important work of social and religious commentary.

Pearl (14th c, anonymous)

A deeply moving allegorical poem, Pearl describes a dream in which a grieving father sees his deceased daughter which is likened to a precious pearl, lost in the ground, in a heavenly paradise. It blends Christian theology with poetic beauty, emphasizing divine grace and salvation.

Parliament of Fowls (14th c, Geoffrey Chaucer)

Parliament of Fowls is a dream allegory that explores love, free will, and social order through a symbolic debate among birds. The narrator, after reading Cicero’s The Dream of Scipio, falls asleep and dreams of a garden of love, where Lady Nature presides over a gathering of birds choosing their mates. The birds symbolize different social classes, with noble eagles representing the aristocracy and common birds reflecting the lower classes. The female eagle’s dilemma—choosing among three suitors—mirrors human debates about courtly love, destiny, and personal choice.

The genre of allegory is also expressed in Morality Plays, where personified virtues and vices convey moral lessons. Notable examples include Mankind, a morality play that depicts the protagonist’s struggle between good and evil, illustrating the challenges of moral choice and redemption, and Everyman, a morality play in which Everyman, representing humanity, is summoned by Death and must seek redemption through good deeds.

Devotional and spiritual literature

Medieval English texts written in this tradition aimed to instruct, inspire, and guide readers in their faith, often emphasizing personal piety, moral discipline, and mystical experiences. Works ranged from biblical paraphrases and saints’ lives to mystical writings and didactic texts and were aimed at both members of religious orders and lay audiences.

In the 13th century, the devotional and instructional tradition produced the remarkable text known as Ancrene Wisse (Guide of Anchoresses), a spiritual guide written for three sisters who chose to become anchoresses (anchoresses, also called recluses, chose to withdraw from the world to live an ascetic life of prayer and contemplation, permanently enclosed in a small cell, or anchorhold, usually attached to a church, with only small openings for receiving food, communicating with visitors, and observing Mass). The text provides guidance on both the external and internal aspects of their religious life, in a surprisingly benevolent tone. It is notable for its vivid metaphors, such as comparing the force of Christ’s love to a medieval version of napalm, the so-called Greek fire!

The 14th century saw a significant rise in vernacular devotion in England, as religious texts and spiritual guidance became increasingly available in Middle English, rather than Latin or French. This shift reflected a growing emphasis on cultivating a deep and personal relationship with God, and direct engagement with religious texts. Rise in vernacular devotion led to a range of mystical and contemplative writing, as represented by authors such as Julian of Norwich, Margery Kempe, Walter Hilton or Richard Rolle.

Julian of Norwich‘s Revelations of Divine Love (14th c)

Julian was an anchoress who wrote the first known book in English by a woman. Her writings are based on a series of mystical visions of Christ that she experienced on May 8, 1373, during a severe illness when she was close to death. She recorded these revelations in two versions: the Short Text, written soon after her experience, provides a direct account of sixteen visions focusing on Christ’s suffering, divine love, and the reassurance that “all shall be well.” The Long Text, written perhaps over two decades later, expands on these visions with deeper theological reflection, emphasizing themes such as divine love, the role of sin in spiritual growth, and the maternal nature of Christ. Her optimistic view of God’s boundless mercy – particularly her assertion that God is never angry at humanity for its sins—a perspective that contrasted with the Church’s traditional teachings on divine justice was groundbreaking for her time, as was her clever reinterpretation of Augustine’s theology.

Margery Kempe (c. 1373–1438) – The Book of Margery Kempe

The Book of Margery Kempe, written in the early 15th century, is considered the earliest known autobiography in English. It recounts the spiritual journey of Margery Kempe, a married laywoman and a mother of 14 children from King’s Lynn, who experienced intense religious visions and mystical encounters with Christ. Unlike Julian of Norwich, who lived in seclusion, Margery led an active and often controversial life, travelling extensively on pilgrimages across England, Europe, and the Holy Land. A central feature of the book is Margery’s extraordinary and uncontrollable weeping, which she believed was a divine gift, signifying her deep love for Christ and sorrow for his Passion and human sin. Her tears, often occurring in public, provoked both admiration and hostility, as many viewed her extreme emotional displays as disruptive or insincere. Despite facing criticism and accusations of heresy, Margery remained steadfast in her faith, seeing her suffering as a reflection of Christ’s own Passion.

Influence

During the Middle Ages, English was significantly shaped by its contact with foreign influences; particularly the Viking invasions and the Norman Conquest restructured its grammatical system and contributed numerous words which made English one of the languages with the largest vocabularies. Itself influenced by other languages, it is nowadays influencing other languages worldwide as a global language and lingua franca. Medieval English literature has likewise exerted a significant and enduring influence as it is evident in the adaptations of medieval narratives within contemporary literature. A notable illustration of this is J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, which draws heavily on his extensive knowledge of Old English literature and culture. Additionally, Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, with its astute portrayals of human character, serves as a crucial link between medieval and modern literary realms. This work has made a substantial impact on subsequent literary traditions, playing a vital role in the evolution of English literature in the centuries to come.

External resources

Dictionaries

- Bosworth-Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary online

- Thesaurus of Old English

- Glossarial Concordance to Middle English

Literature

- Collection of edited Middle English texts

- Database of Middle English Romanceshosted by the University of York: This database is specifically useful for the comparison of different versions of related late medieval texts.

- Electronic Beowulf

- Database of English and Irish medieval texts

- Companion to the Canterbury Tales

- Manuscripts of the West Midlands